How the Art of Gaman affected me personally:

Gaman is a Japanese word that means to endure unspeakable suffering with dignity and grace. My sister Dawn, her husband Rowland, my dad and I visited the Renwick Gallery over the weekend. Dawn digitally recorded my mom's reactions to the artwork. I hope to post my mom's voice recollections soon.

One of my high school research projects was to visit the National Archives. There I located documentation about the internment of my mom's family during World War II. Later, after monetary reparations were paid in the mid 1980's that documentation helped me secure payments from the US Government of $10,000 per individual on behalf of my mom, two uncles, and my grandmother. In high school, what I learned about the indignities my mother suffered as a child forever changed me.

|

| My grandfather's arrest order |

How the Art of Gaman affected my mother:

Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941, my grandfather, Yunoksuke Tsuchitani, like many other business and community leaders, was taken in the middle of the night by men wearing dark suits. At the exhibit, my mom remembered that my grandfather had been wearing only the clothes on his back -- without a coat, he was taken to a military prison in Bismarck, North Dakota. There, because of the freezing conditions, he lost his hearing. Later, he was transferred to burning hot Lordsburg, New Mexico. My mom, 6 years old at the time, did not see her father again for over 3 years. The family was reunited at Tule Lake as the war was ending.

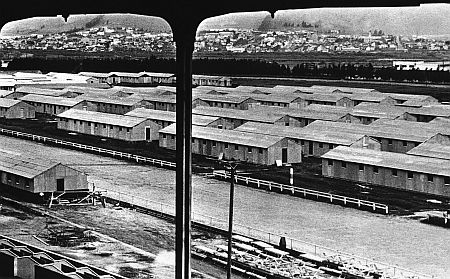

As a 6 year old child, my mom witnessed her mother burning all their household possessions after receiving the evacuation notice, which was prominently displayed at the exhibit behind a flag of red, white, and blue cranes. Photographs of Tanforan Racetrack at the entrance reminded her of the smell of horse manure. Her grandparents, her aunt Pepe's family, her mom, her two baby brothers Isamu and Ken, and she were herded into horse stalls, divided from the other families by sheets.

(http://www.vpr.net/news_detail/85905/

(http://www.vpr.net/news_detail/85905/The Obata drawing of a dust storm from inside a barack reminded her of her own hastily constructed dusty barack in Topaz. She recalled how some of the women would laugh at her grandfather, who occupied his time by cleaning the camp toilets. He always had a set of mops leaning against the barracks.

I remember my mom telling me long ago about the many ways that children found ways to amuse themselves. The collection of birds hand carved from scrap wood, with each feather carefully painted, reminded her about how she used to tame wild birds; one of her pet birds loved shiny objects and constantly flew home with other peoples' jewelery. She remembered the awful look her mother had when she came home to discover her bird had electrocuted itself while tugging on an electric cord. Another source of amusement I remember her telling me about was how she and her brothers used to catch polywogs in the drainage ditches, then watch them develop into frogs.

The Shintaka shell pins reminded her of how her grandmother and aunt also used to make these kinds of pins while at Tule Lake. She remembered collecting shells for them.

The collection of walking staffs reminded her of the ironwood staff her father had sanded to perfection. Lightweight, thin, and perfectly straight, her father's walking staff was strong enough to carry a load of luggage.

One artist heated triangular files in a potbellied stove and pounded them with a hammer to make the chisels that he used to carve a traditional Noh Mask. These artists were given neither tools nor materials. Still, artist after artist found a way to create art from nothing but scraps.

An idea for a book:

As an undergraduate at Georgetown University, during my senior year, I took a course called US in the 20th Century under Professor Dorothy Brown. I wrote a paper called Rising Son in the West, about how my grandfather, an orphan, rose from rags to riches to became one of the wealthiest men on the West Coast. I spent my Christmas Holidays in 1984 in the Library of Congress reading California newspapers to learn how a climate of racial discrimination led to the internment of Japanese Americans. Today, I am noticing a similar climate of fear and discrimination directed toward a wave of recent immigrants from south of the border.

The story of Yunosuke Tsuchitani is a Horatio Alger story with a dark side. He was born on the island of Iwaishima in 1899, 99 years before my son Joseph was born. My grandfather was an orphan at age 9. As a child, he earned money by writing letters for illiterate adults. In 1917, as a member of the Japanese Merchant Marines, he came to America on a tall ship. He jumped ship in San Franciso Harbor and swam to shore in shark infested waters. His brother Ruyiji, who had left the island first, bribed the immigrations official.

Starting as a busboy, studying English at night, my grandfather rose to a management position in the Pacific Trading Company. He later owned a successful restaurant located near a military facility, which he sold in order to found the White Star Tuna Company. After labor problems shut him down, he later sold out to a company that became Chicken O' The Sea. While recovering from depression, he found the inspiration to create a market for straw flowers. He invented a system for attaching wire to the flower heads, allowing them to be shipped East via the Union Pacific Railroad. He created a complete grading and marketing system that enabled many Japanese farmers in the Bay Area to become fabulously wealthy by growing strawflowers instead of tomatoes. He was known as The Straw Flower King.

Before Pearl Harbor, my grandfather owned a fleet of ocean going yachts. The Di Maggio family took care of his boats.

Like many Issei (first generation people from Japan), my grandfather had been sending money home for many many years. A community leader, he contributed to charitable causes; one of those charities was a fund for the widows and orphans of soldiers. Contributions to that charity provided the legal basis for his incarceration.

As an Issei, my grandfather had been prohibited by California Law from buying land. My grandmother, who was Nissei, had signed her name to help relatives purchase land, but had refused to sign on behalf of my grandfather. At the time of his arrest, all of his financial assets were invested in his business. His boats were burned. He left America penniless.

In war torn Japan, my grandfather found himself and his family dependent upon the charity of relatives. As I prepared to give a speech at my grandma's 80th birthday (17 years ago), my mom told me about a harrowing boat ride she took during a storm from Iwaishima to the mainland as she accompanied her mother on her first job search.

In war torn Japan, my grandfather found himself and his family dependent upon the charity of relatives. As I prepared to give a speech at my grandma's 80th birthday (17 years ago), my mom told me about a harrowing boat ride she took during a storm from Iwaishima to the mainland as she accompanied her mother on her first job search.

In the camps, my mom had used a dictionary to teach herself how to read. With only three years of formal education, while attending a Methodist School in Fukuoka, Japan, my mom received a full scholarship to the University of Nebraska. In her application letter, she quoted Nietzsche.

A quote from Nietzsche:

A quote from Nietzsche:

a

[Anything which] is a living and not a dying body... will have to be an incarnate will to power, it will strive to grow, spread, seize, become predominant - not from any morality or immorality but because it is living and because life simply is will to power... 'Exploitation'... belongs to the essence of what lives, as a basic organic function; it is a consequence of the will to power, which is after all the will to life.

from Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil, s.259, Walter Kaufmann transl.

This is an amazing story, and more so because of the personal connection. I would LOVE to see this in a book. I have been researching the Japanese-American interment since 1988, and would like to see more personal histories unveiling the experiences that many non-fiction books lay claims to.

ReplyDeleteThank you for your kind response. My grandmother’s side of the story is equally fascinating -- perhaps more so. At 22 she married a far older fabulously wealthy man in an arranged marriage. After the war, she became the primary caregiver and breadwinner. Alice (Masako) Tsuchitani is 97. She still possesses all of her mental faculties.

ReplyDeleteMy grandma would be a great person to interview if you are in San Francisco – she’s one of the last of the Nissei. She became an interpreter for the US military. She had a talent for sweet talking people into giving her gifts, especially extra flour – if you meet her, you’ll find she still has that talent of getting people to do things for her!

The flour was riddled with meal worms. My mom won’t eat donuts to this day – she associates donuts with the bitter taste of mealworms.

In college, I became interested in my family tree, and learned a great deal about the Otsuka side of the family in the process. The other night, I saw a picture of an Otsuka family assembling at Tanforan Racetrack. It quite possibly was my mom’s aunt’s family.

Here’s another thing that is really strange. During the Korean War, my father commanded a radar installation on a small island off the coast of Kyushu for the Strategic Air Command. When he ordered supplies, Alice was on the other end of the radio. My father decided to leave the Air Force because he disagreed with the decision to go to war in Viet Nam. As he was leaving the Air Force, my father was stationed at Lincoln Air Force Base in Nebraska. His roommate happened to be dating my mother’s roommate while she was attending the University of Nebraska. Small world!

I would one day like to visit Yamaguchi Prefecture. I hope to find a scroll dating back to the Gengi-Heike War from a Samuri from the losing side thanking one of my Tsuchitani ancestors for rescuing him from the Japan Sea.

Daniel, this is all so fascinating. I remember doing a high school paper on the internment camps based on the paper you had written and the documents you had collected! It's so nice that you've done all of this research so that our family's history isn't lost.

ReplyDeleteYour Cousin Rachel

Oh wow! First, was your grandmother the only woman who served as an interpreter for the military during WWII? Because throughout my research, I haven't come across any! Second, life is certainly full of ironies! Keep us informed about the development of your book! And third, I will take that in consideration in interviewing your grandmother. I'm glad I "stumbled" onto your blog.

ReplyDelete